Blogs

September 16, 2021

Living Security Community's Blog Contest Winner: Are You Waving the Wrong Red Flag?

The Living Security Community is excited to announce Peter Kirwan as the winner of our recent blog submission contest! Peter is an IT Support and Training specialist and an emerging expert in the field of the human factors of cybersecurity. Peter was recently awarded his Masters of Science with Distinction in Computer Systems Management from Heriot-Watt University, where he completed a dissertation on "Security training, gamification, and memory."

The Living Security Community is excited to announce Peter Kirwan as the winner of our recent blog submission contest! Peter is an IT Support and Training specialist and an emerging expert in the field of the human factors of cybersecurity. Peter was recently awarded his Masters of Science with Distinction in Computer Systems Management from Heriot-Watt University, where he completed a dissertation on "Security training, gamification, and memory."

Read Peter's winning blog post below then check out Living Security Community—a place where cybersecurity and IT professionals like Peter can share resources and discuss the topics most important to them.

Are You Waving the Wrong Red Flag?

So, you have a security awareness program but when did you last check the phishing content? Maybe it was once innovative, but times and attacks change so our training should too. What if some of the anti-phishing advice in there is outdated and now doing more harm than good? Let’s look at some popular anti-phishing advice, why some of these “red flags” should be consigned to history’s dustbin, and how we can do better.

“Check for Typos and Poor Grammar”

Over 45% of publicly available anti-phishing pages tell users to beware of emails with typos and poor grammar (Mossano et al., 2020). This is perhaps why if you ask a random person on the street to describe a phishing email, they’ll probably think of messages from a Nigerian Prince riddled with spelling and grammatical mistakes requesting urgent help transferring funds. Leaving aside attackers making deliberate errors to hook only the most vulnerable among us, the attackers eyeing up your organization simply don’t make mistakes. They might not be native English speakers but, between automated tools like Grammarly and cheap third-party proofreading services, there’s no reason for them to misplace so much as an apostrophe. If they are just worried their writing doesn’t quite “flow”, there are specialist editing services that promise a full refund if the click-through rate doesn’t improve. The phishing emails that survive your technical controls will usually be in perfect English.

“Check the Layout”

Over 11% of publicly available anti-phishing pages tell users to look out for poorly designed emails or webpages (Mossano et al., 2020). Here’s a direct quote from the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre.

“[Attackers] will try and create official-looking emails by including logos and graphics. Is the design (and quality) what you'd expect?”

Here’s the problem. This is how easy it is to create an official-looking landing page with the design and quality that users expect through cloning using the phishing simulator GoPhish.

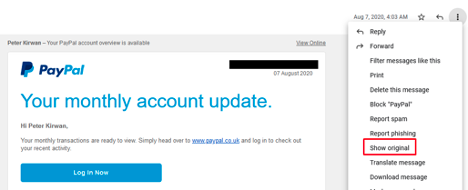

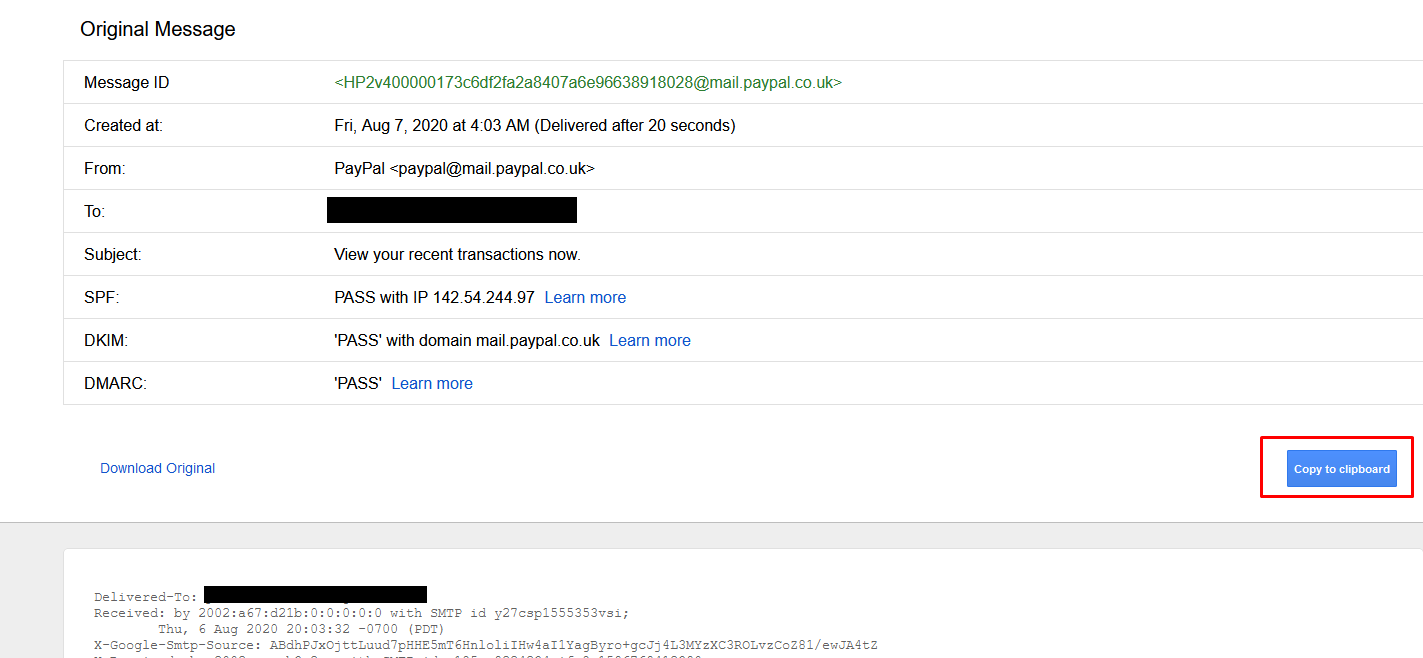

Want to clone an email? Just open an email from the target company and get the source code. Here’s me retrieving the source code in Gmail. It’s just three steps…

Then just paste it into your phishing editor.

It really is that easy and, hey, if the attacker clones like this they don’t even need to worry about proofreading. No self-respecting attacker will use anything less than a picture-perfect email and landing page.

“Look for the HTTPS Padlock”

It’s 2021. According to The APWG Phishing Activity Trends Report, 83% of phishing sites use HTTPS and yet over 23% of anti-phishing pages are telling users that the lack of HTTPS is a red flag (Mossano et al., 2020). We can do better.

Checking the Sender: Moving Past “Stranger Danger”

We should still tell users to check the sender though right?

Well yes … but it matters how you do it. Done badly, this red flag can cause more harm than good because there are just so many ways to spoof a sender's address.

We need to go beyond just telling users to “check the sender” and show them how. We need to explain the difference between display names and sender email addresses. We need to explain how display name spoofing and lookalike spoofing of email addresses work. If your organization has DMARC, DKIM, and SPF properly set up, then your users mostly don’t have to worry about exact address spoofing. If you’re unsure what those acronyms mean, please take a moment to learn about how you can quickly and easily set them up for a big security win.

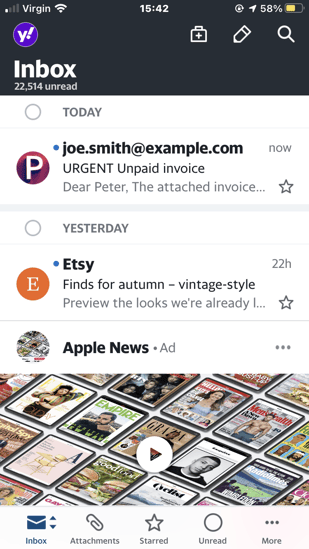

Without this added depth we risk users on mobile devices, for example, seeing something like this from “joe smith” in preview and thinking it’s safe because they believe they’ve checked the sender…

Display name spoofing is disturbingly easy and in Gmail, for example, it can be turned on through the normal account settings. Attackers can even include an email address in the display name so users think they’ve seen the address when they were only looking at the display name. There are some technical controls to mitigate this but none of them are perfect.

Maybe all this seems obvious to you. To many, it’s clearly not. Though 40% of publicly available anti-phishing webpages told users to check if the sender was “unusual or unexpected”, none of them warned about the possibility of spoofing (Mossano et al., 2020).

Oh and the other thing they didn’t do? They didn’t think to mention that the sender might look legitimate because it's coming from a hacked company inbox as often happens with Business Email Compromise.

What’s the Harm?

Maybe these are only some of the red flags you tell users to look out for. If so, it’s tempting to think that there’s no harm in raising them. It might seem like it’ll help users spot some of the more primitive phish while they can use other tips to spot more advanced attacks. After all, it’s not like you ever said that any polished-looking email with zero typos and a legit-looking sender was safe… right? Just because you didn’t say this, doesn’t mean your users didn’t hear it though.

Given red flags to check for danger there’s often a natural tendency to take the absence of any one red flag as a reason to feel safer. Let’s say I’m camping after recently watching Liam Neeson in the wilderness film The Grey and as a result, I am particularly worried about wolves. Searching out some expert advice about wolf red flags, I look out for wolf tracks, wolf droppings, a wolf den, and animal carcasses where large bones appear bitten through. Let’s say I’m extra diligent and check all these signs. Now, logically, of course, none of these is by themselves a necessary indicator of wolves. There might, for example, be no recent droppings because wolves have only recently come into the area. The way the mind works, though, my confidence increases with each red flag that I find to be absent. No droppings? Feeling a little better. No tracks? Feeling even safer.

Unlike my camping trip, your users often won’t run through all your red flags when they encounter a phishing email. If you’re lucky, they’ll check one or two. The worry is they look for typos, layout mistakes, or HTTP, and the absence of these increases their confidence in an email’s safety. The red flags then become green lights and that is how your training can make it more likely that users click on phishing emails.

What To Do? Focus On What’s Hard To Fake

The solution is to switch our focus to things that are hard to fake and red flags that won’t become green lights.

Checking Links

Some phishing emails don’t have links but, for those that do, train users to check links on both desktop and mobile devices. Links are probably the hardest element of an email to fake. Sure attackers can hide a dodgy URL behind anchor text like this where the anchor text suggests google but the link goes to Facebook.

Or behind an image like this:

Ultimately, though, if the user knows how to check, then the dodgy URL, or the suspicious link shortener in front of it, will be revealed.

Again, how you do this matters. It’s not enough to tell them to hover. You need to tell them how to look for the true destination URL behind anchor text/elements on both desktop and mobile devices. It’s also not enough to get them to just look at the destination URLs, they need to know how to read them.

The bad news? Research shows that most users struggle to recognize the root domains that show a link's actual destination (Albakry et al., 2020). So you’re going to need to invest some resources to make sure users understand how to quickly pick out the root domain from something like this.

https://www.ups.delivery.net/gb/en/Home.page?WT.srch=1&WT.mc_id=ds_gclid:EAIaIQobChMIsKGVurDY8AIVB5eyCh36Wgc_EAAYASAAEgK-zfD_BwE:dscid:71700000050016000:searchterm:ups&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIsKGVurDY8AIVB5eyCh36Wgc_EAAYASAAEgK-zfD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

The good news is that I’ve got a short (albeit slightly cringe) game that will teach them just that. It’s yours to use for free with attribution and the Qualtrics code is available on request if you’d like to build your own version. Check it out here https://peterkirwan.co.uk/phishgame (redirects to https://hwsml.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3g5Imw87sGwTy3Y).

Checking for Use of Social Engineering Principles

What about emails that don’t contain links where the attacker is, for example, trying to talk someone into transferring money.

The best thing here is to get users used to spotting Cialdini’s six principles of persuasion used in social engineering (Cialdini, 2007).

Let’s quickly review these:

Authority

The email contains an “order” from some more senior members of the organization’s hierarchy. For example, a request for a transfer of money appears to come from the CEO.

Consistency/Commitment

The email justifies its request on the grounds that such requests are normally granted. An attacker might argue, for example, that Janet in accounting approved a similar request just last week.

Reciprocity (A.k.a Quid Pro Quo)

The user is persuaded to give something to the attacker under the illusion that the attacker is already doing them some sort of favor. A common example of this would be an attacker asking for credentials in order to (supposedly) fix a technical problem the user is having.

Liking/Similarity

We like to do things for people that we like and often some sort of affinity will gain our affection. For example, an attacker might claim to follow the same sports team as a target.

Scarcity

We are more inclined to do something if we think we have a rapidly closing window in which we can do it. Attackers may simulate this rapidly closing window of opportunity by, for example, suggesting that money must be transferred within the hour otherwise a major deal will fall through.

Social Proof

We care about the opinions of others, especially people we know. An attacker might exploit this by, for example, pretending to have some sort of relationship with someone close to the target, e.g. a friend of their father.

Training users to spot these principles of persuasion has two advantages. The first is that, unlike most other red flags, these red flags are out in the open. If someone is appealing to their authority, for example, it’s clear that is happening. If it wasn’t, then appeals to authority wouldn’t be nearly so effective. The second advantage is that training users to look for these principles will not only help protect them against phishing but will make them better able to handle attacks from a range of other vectors including vishing and in-person social engineering. If you can spot the use of scarcity in an email, you can spot it on the phone and when someone says they need urgent access to a building.

Wrapping Up

That concludes our tour of red flags that should be put away in a drawer and what to focus on instead. Found something you disagreed with? Let us know in the Community.

Oh and statistically we are more of a threat to wolves than they are to us. https://wolf.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Are-Wolves-Dangerous-to-Humans.pdf

References

Albakry, S., Vaniea, K., & Wolters, M. K. (2020). What is this URL’s Destination? Empirical Evaluation of Users’ URL Reading. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376168

Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. Harper Business (Revision Edition).

Mossano, M., Vaniea, K., Aldag, L., Duzgun, R., Mayer, P., & Volkamer, M. (2020). Analysis of publicly available anti-phishing webpages: Contradicting information, lack of concrete advice and very narrow attack vector. 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1109/EuroSPW51379.2020.00026